BSA VICTOR 441cc / 1966

This perfect example of the first year model of the BSA Victor was the replacement for the famous Gold Star model. The Victor is smaller in cubic centimeters (441cc as compared to 500cc) and also smaller in physical size. This machine became very popular on and off the track.

My brother Dan purchased a Victor when he was a senior in High School. I have two distinct memories from the time he owned this bike – him wheeling it over backwards in the school parking lot and his nearly braking his leg trying to start the bike when he was leaving work. The ’66 model was particularly hard to start unless it was in perfect tune. Later models went away from the ET ignition, had 520 chains (instead of 428), longer seats, and other concessions to comfort as opposed to serious off-road use.

Please enjoy this ’66 model BSA Victor (I only wanted a ’66) that was meticulously restored by Don Harrell.

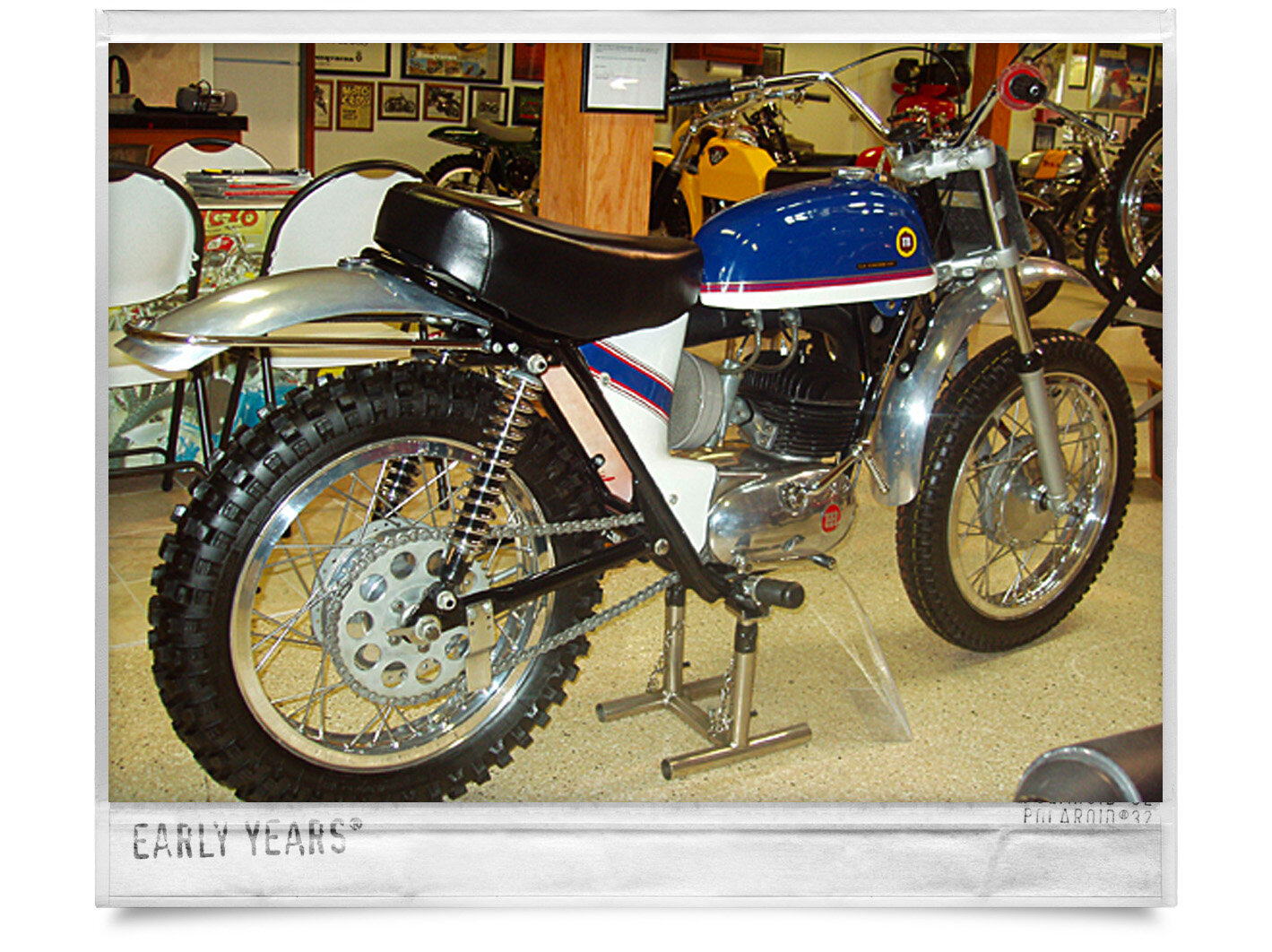

SPRITE/AMERICAN EAGLE 405 TALON / 1971

American Eagle arrived on the USA motocross scene in 1967 with a big ad budget and small racing team (that included a young Brad Lackey). But, in truth, there was no American Eagle motorcycle factory. The American Eagle was a private-label bike that was built by Sprite Developments in Oldbury, England by Frank Hipkin. Brits could buy the bike as the Sprite 405 Talon, Americans were offered the bike as the American Eagle 405 Talon, Australians knew it as the Alron 405 and Belgiums thought it was the BVM 405. All the bikes were identical, with the exception of the American bikes having “American Eagle” cast into the engine case. Amazingly all the different national distributors tried to pretend that the Sprites were designed in the home countries. It wasn’t until many years later that each country learned the truth about the “other” Sprites.

Most distressing of the “clone engineering” behind the $1195 American Eagle 405 Talon was that the engine itself was a clone. It was an Italian-built copy of a late ‘60s, four-speed, 399cc, Husqvarna engine. Many Husqvarna parts would fit in the Italian engine, but not all. Most American Eagles racers remember the gearbox with particular distaste. Additionally the Talon had a Sprite-built fork that was a direct copy of a Ceriani fork.

Sprite Developments in England showed rapid growth from 1964 to 1974. Owner Frank Hipkin started building lightweight, Reynolds tubing frame kits for Villiers, Triumph Cub, Husqvarna and Maico engines. Amazingly enough, if Hipkin had kept the Sprite motorcycle company small he might have lasted longer. Success killed the Sprite, Talon, Alron and BVM. When Hipkin started exporting Sprites in large numbers the British government closed the tax loopholes that Sprite was using and, following the collapse of the U.S. American Eagle distributor (Galaxy Wholesale in Garden Grove, California), the financial losses were too great to absorb.

Today, Sprite Development still exists, but it builds RVs, caravans and motor homes.

WHAT THEY COST

Although it was quite rare to find the Sprite or it’s stepchilds on EBay, collectors don’t seem to be drawn to them. This un-restored example was purchased in 2006 for $2600. A good core (original but in need of restoration) Husqvarna of the same year would easily go for twice this amount.

MODELS

Eagle 125 – CMXR (125cc Sachs engine), Eagle 250 – GMXR (250cc Husqvarna clone), and the Eagle 405 – TMXR (405cc Husqvarna clone).

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

The Eagles came with several different fuel tanks (2.0gal or 2.5gal) made of either fiberglass or aluminum and either Dunlop Sports knobbies or trials tires. The side panels are aluminum as are the fenders and the front and rear hubs are polished aluminum. If these items are in good shape, the bike will make a beautiful addition to any collection.

PARTS SUPPLY

It is very difficult to find parts for the Sprites. Vintage Husky in San Marcos, CA at 760-744-8052 may be able to help. In Europe, try Frans Munsters at vintage@fmunsters.nl.

AJS 250cc STORMER / 1972

So what was more logical for the born again Norton Villiers company of the mid 1960’s than to create and launch a purpose built motocrosser hot on the heels of its successful Norton Commando. The Stormer was based around a re-engineered version of the agricultural Villiers 2-stroke engine which had long been the mainstay of British 250 class competition.

Top British riders, Andy Roberton and Malcolm Davis were the development riders and a prototype was being raced as early as 1967, with first production in 1968.

The chassis featured several innovations that were way ahead of their time such as leading axle forks and the rear shock mounts mounted forward on the swingarm. Unfortunately, the dated Villiers engine kept the Stormer from being a strong seller.

To this day, new and never ridden Stormers, still in the crate, show up in the marketplace. Unfortunately for me, not finding one of the new (and in the crate) examples when I was ready to buy, this bike was restored by Vintage Iron at significantly more cost.

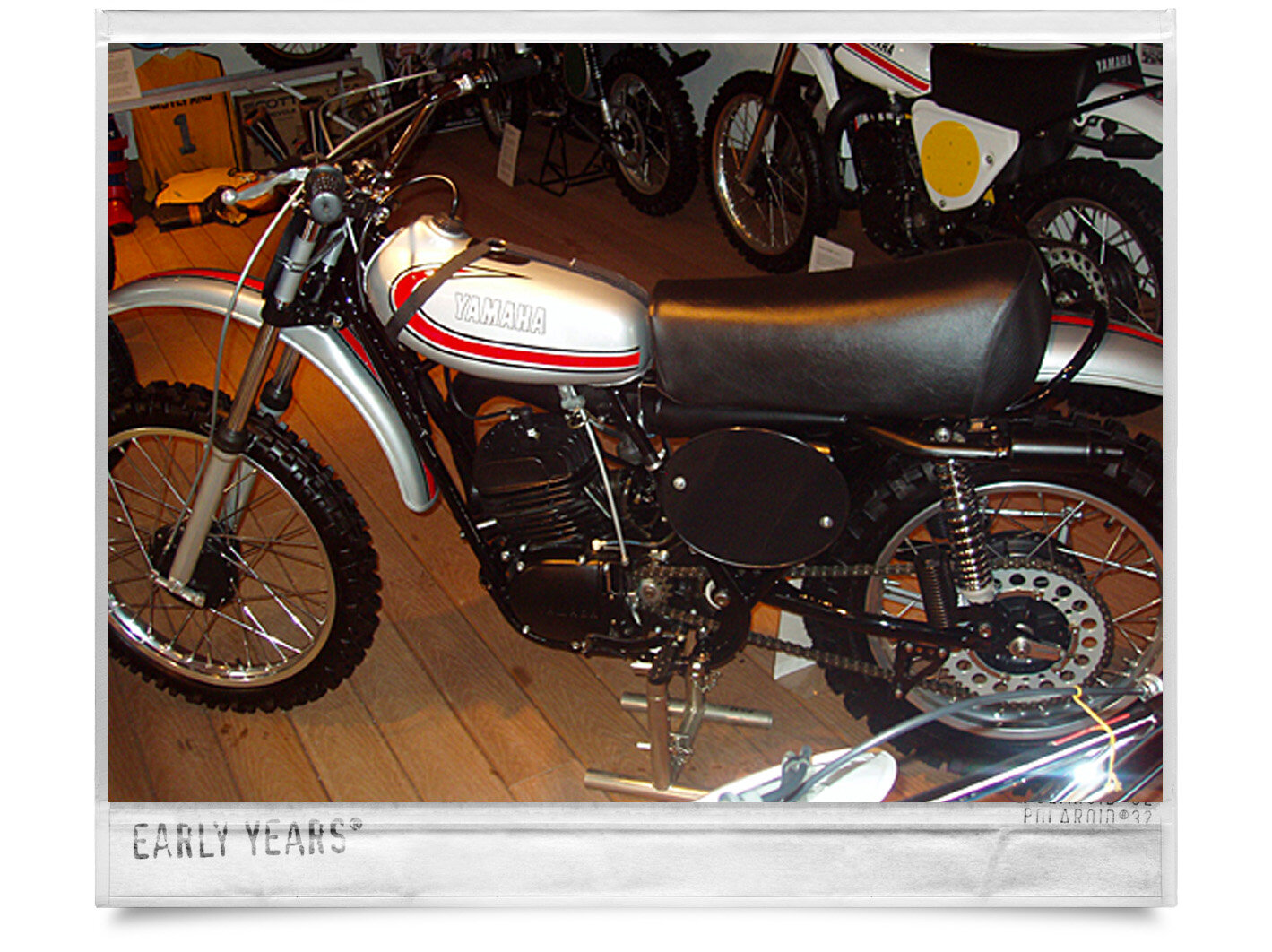

AMMEX 250cc MX / 1976

Gary Jones won four consecutive 250 National championships while racing for Yamaha, Honda, and Can-Am. When he suffered a leg injury at Daytona and Can-Am bought out his contract, Gary took the $70,000 and started his own motorcycle company. Not an easy task, but at the time, Cooper Motorcycles was going out of business, and the Jones family bought the Mexican based company and used the Frank Cooper designed enduro bike as a prototype for the first Jones-Islo (the name would later be changed to Ammex, which stood for American-Mexican).

Under Mexican law, 68 percent of the Ammex had to be manufactured in Mexico, so the pieces that would be out-sourced included Sun rims, Diamond chain, Mikuni carbs and ART pistons. To ensure that the Mexicans didn’t use pot metal in the castings and frame, Jones shipped American-made chromoly and aluminum to the Saltillo, Mexica, Moto-Islo factory. The Mexican metallurgy was always suspect, especially in the crankshaft and transmission.

The Ammex borrowed its plate-style shift system from Maico, the dual-use kickstarter/shift shaft from CZ and a Yamaha YZ250 top-end could be slipped right onto the Ammex cases.

Ammex had high hopes, but unfortunately the Mexican peso was devalued-dropping from 12 pesos to the dollar to 120 pesos in less that a week. Since Ammex was a Mexican company, it was worth one-tenth of what it was the week before. Gary Jones lost his money and his dream of building his own motorcycle. Productions dribbled on a few years, but after the devaluation in 1976, the company was doomed.

BRIDGESTONE SR175 TWIN / 1967

By the 1960’s, Bridgestone was a one of Japan’s largest companies, building cars, bicycles, motorcycles, and of course – tires. The motorcycles were technically a step above the competition, but the higher price and the choice of Rockford Motors in Rockford, Illinois as the distributor probably hurt sales. By 1971, Bridgestone was out of the motorcycle business.

The SR175 was a hand assembled factory racer, with features like dual rotary valves, polished ports, stuffed crank and a tube steel frame. Quarter mile performance was listed on the brochure as 15.3 seconds – fast!

It’s amazing that this model never really took off in popularity; especially in scrambles were there was a 200cc class.

This machine is unrestored and in original condition. Check the tires – very little time on this little jewel.

BSA B50MX 500cc / 1974

The BSA Factory (Birmingham Small Arms) built the B50 in answer to the growing demand for a good 4-stroke off-road bike. The 500cc thumper made a good trail bike, but was too heavy to compete against the modern 2-strokes. Chuck Minert used to race a B50 that was heavily modified with significant success in local motocross and scrambles events. I purchased a new B50 and won the 1975 Dinosaur Run Scrambles, and important 4-stroke only event in the day. I had modified the bike extensively and remember the bike as a blast to ride.

This bike was purchased from a gentleman in New Mexico and comes with a great story. The father of the man I purchased the bike from loved BSA’s, so he purchased two identical 1974 B50’s, one to ride and one to sit in his living-room. The machine you see here was the living room bike, and according to the seller, this bike has never been ridden or started. Kind of the “Holy Grail” of vintage dirt bikes as restoration was not necessary. Please enjoy!

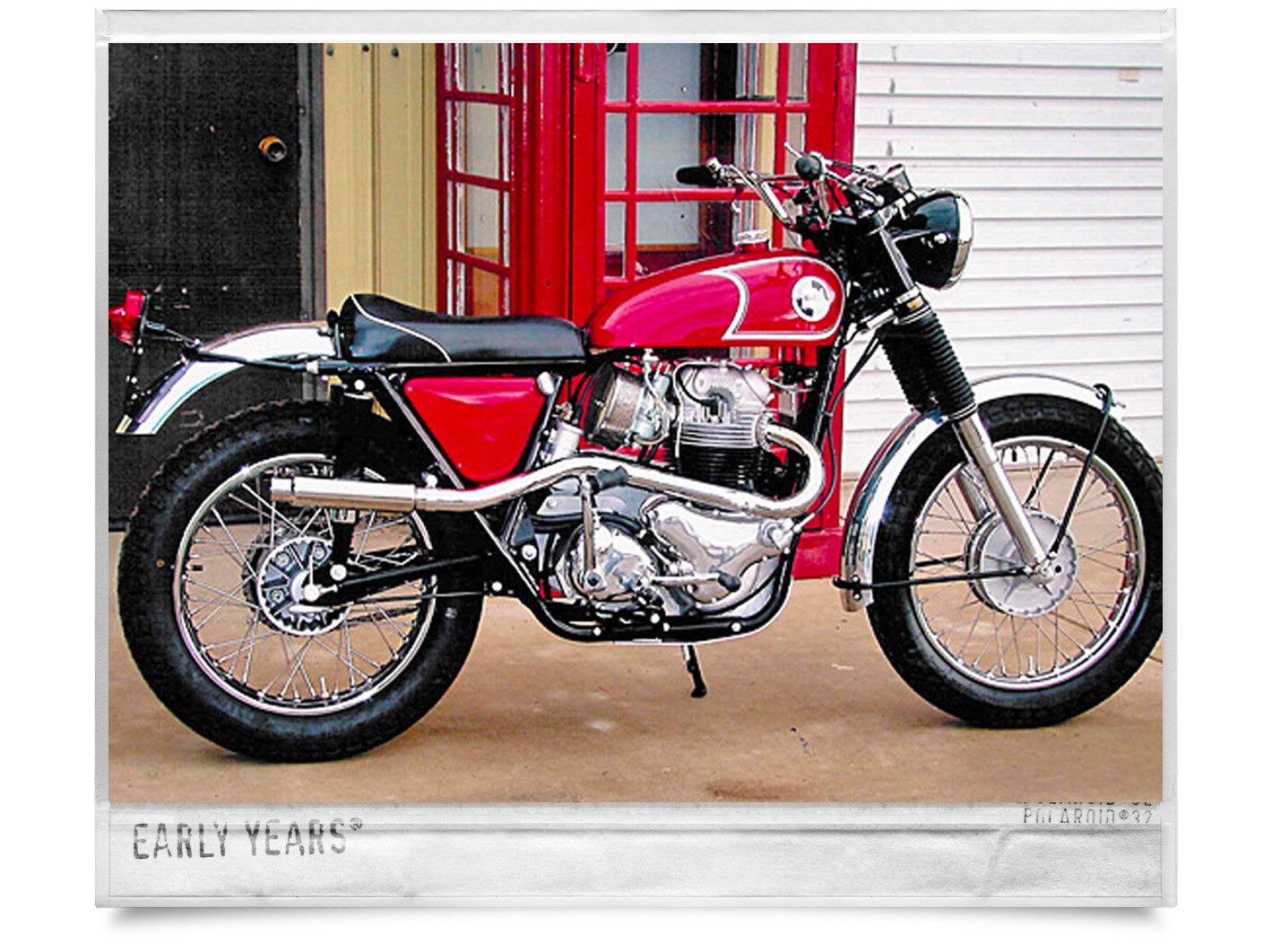

BSA 650cc HORNET / 1967

The Hornet model was introduced into American to compete against the very successful Triumph TT Specials that had been tearing up scrambles courses from coast to coast. One of my early hero’s, Dallas Baker had a fair measure of success on one of these Hornets raced out of Irv Seaver Motorcycles in Santa Ana. Dallas was one of the first Ascot Pros that Dan and I had the opportunity to meet. I remember watching Dallas at Ascot and Irwindale and dreaming of racing at his level.

This machine was restored by British expert, Don Harrell. Don’s attention to detail is phenomenal. Every nut and bolt was stripped, filed, and cad-plated (the proper plating for English hardware) to better than new condition. The engine was also completely disassembled and rebuilt with new parts as necessary. The frame was powder-coated and all body work repainted as original. Don has restored several of the bikes in my collection. Please enjoy this “really good restoration,” by one of the best in the business!

BSA B44 METISSE 500cc / 1968

The Rickman Metisse frame was the “State of the Art” chassis in the mid to late 1960’s. The BSA B44 engine with Westlake top end was arguably the lightest and most powerful engine available. When mated together, the Rickman B44 was still competitive against the new lightweight CZ’s and Huskies that were the standard in 500cc International GP’s. To this day, in AHRMA (American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association) events, several competitors prefer this motorcycle because of its tractable power, lightweight (for a 4-stroke), and precise handling.

This machine was built by my friend, Frans Munsters of Veghal, Holland. Frans, the founder of the leading motocross air filter company, Twin Air is a collector and restorer of vintage dirt bikes. This machine is one of four bikes that I have purchased from him and imported into America.

BSA GOLD STAR CATALINA SCRAMBLER / Chuck Minert / 1959

959 BSA 500cc GOLD STAR “CATALINA SCRAMBLER” – DESERT, SCRAMBLES, ROAD RACING………..IT COULD DO IT ALL!

The BSA Gold Star Catalina Scrambler was the perfect machine for a rider like AMA Motorcycle Hall of Famer – Chuck Minert. Minert excelled in all types of motorcycle racing from speedway to trials, from desert racing to scrambles, and later, in motocross. In the late 50’s and early 60’s Minert rode a factory -backed BSA for much of his racing career and was loyal to the British brand long after the bikes were past their competitive prime.

The most important win for Minert in his racing career came in 1956 at the popular Catalina Grand Prix. Almost 1000 riders competed and the win at Catalina was so prestigious, that BSA actually named the 1969 Gold Star DBD34 after the event, thus the name “Catalina Scrambler!” The machine he rode was a 1956 BSA Gold Star Scrambler! Chuck comments, “I changed the tank to a 5 gallon, borrowed a front brake backing plate with a scoop (for additional cooling), and used a 19″ front wheel instead of the standard 21″ wheel preferred by the English!”

The westcoast distributor for BSA, Hap Alzina asked the factory for a replica of this bike! By the late 1950’s, the US market was the strongest in the world for BSA and they followed his advice and responded with the Catalina Scrambler in 1959. The machine would go unchanged until its production stopped in 1963.

The aluminum barrel Gold Star was arguably the most successful race bike every built. It won races for over a decade in every discipline………desert, scrambles, motocross, flat-track, and roadracing! Ultimately, the Gold Star model was replaced by the smaller (and lighter) B44 that was developed by motocross World Champion – Jeff Smith. This machine, based on the BSA 250cc model, would win its final 500cc Motocross World Championship in 1965 and would mark the end of 4-stroke domination in the premier series.

BSA BANTAM 175cc TRAIL BRONCO / 1965

When BSA (Birmingham Small Arms) introduced the “Made for USA” Trail Bronc in 1964, the companies ads professed the Bronc was “Ideal for those who want to go wilderness wondering, for hunting trips, or just exploring off the beaten track!” and included a picture of the machine loaded in the back of a station wagon. The ads caption said “Fits your station wagon or car trunk!”

The BSA Bantam was based on the tried and proven 175cc 2-stroke engine machine that was initially introduced in 1948. Though the little 2-stroke was built in BSA’s Birmingham factory, the actual design was a German design (DKW RT125) which was received as part of the World War II reparations. Similar designs knocking off the German DKW were also built by the USSR as the Moskva and by Harley-Davidson as the Model 125. Exact production numbers are not known but estimates range from 250,000 to 500,000 units that were produced by BSA from 1948 till 1971.

One thing BSA had not expected was the Bantams introduction into competition events. Owners modified their Bantams, fitting non-standard sprockets and wider handlebars. BSA responded with a trials model and later the Trail Bronc which was a stripped down version of the D7 Bantam that was introduced in 1963. Dunlop 300 x 19 tires, semi up-swept exhaust (BSA claimed it was free-flowing), high ground clearance, stripped down equipment which included no front fender, and an additional large trail-sprocket were standard equipment with this Bantam. Another feature that was a concession to off-road riding was the folding footrests. Power output from the 3-speed 175cc engine was a claimed 8 horsepower using premixed oil and petrol.

The Western USA BSA importer – Hap Alzina in Oakland, California had asked BSA to build this machine for the U. S. market. Though this seemed like a good idea, Yamaha introduced the YG1 80cc trailbike at the same time and Hodaka would soon introduce the Ace 90. Another factor resulting in poor sales was the BSA dealers focus on the much larger 500cc and 650cc 4-stroke machines primarily intended for street use. The result was many Trail Broncs sat in the dealer show rooms and some – like the pictured example, were never sold!

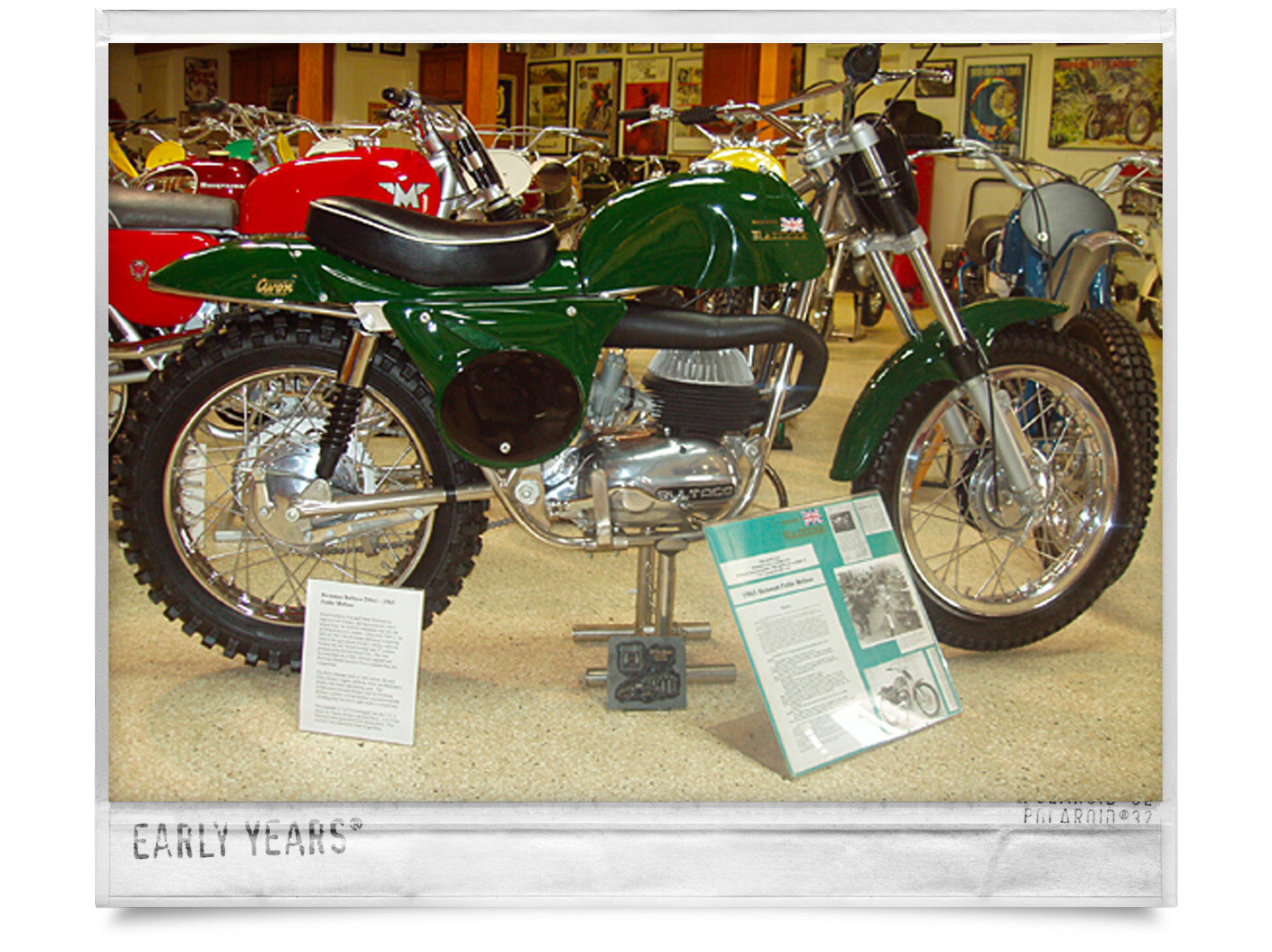

BULTACO 200cc MATADOR / 1964

A Spanish roadracing champion both before and after the war, Francisco Xavier Bulto co-founded the Montesa company in 1946. He resigned his directorship after a board meeting voting to retire the factory from GP road racing in 1958. That same year, with other former members of the Montesa firm, he began tooling up for a new motorcycle which was announced early the following year as the Bultaco, a name suggested by Bulto’s friend – John Grace. A “Thumbs Up” would become part of the Bultaco logo.

In 1964 Bultaco introduced the Matador 200. The machine was designed to compete in the International 6-Days Trials which was considered to be one of the toughest tests of a motorcycle and rider. With a full compliment of street legal equipment – ie, horn, lights, etc. the bike appealed to many street riders that liked to ride both on and off-road. The machine used the premier Betor rebuildable suspension components, Akront rims, and had a peak horsepower of 23 hp. The Matador would open up an all new market for a dual-sport motorcycle.

This machine was restored by Bob Benson, a Bultaco expert from Massachusetts and is quite rare. Please enjoy!

RICKMAN BULTACO 250cc / Petite Metisse / 1965

British brothers, Don and Derek Rickman as importers for Bultaco, and top motocross riders helped forge the Spanish companies way into the growing motocross market – circa early 1960’s. As early as 1963, Don Rickman delivered a crippling blow to the agricultural British 2-strokes when he became the only British finisher and 3rd podium position at the British Grand Prix. This was accomplished on a 196cc Bultaco engined and Rickman framed machine 50cc’s smaller than the competition.

The Petite Metisse, built in 1965 utilizes the new 250cc Bultaco engine, perfectly fitted into Rickman’s jewelry like frame and running gear. The collaboration between Bultaco and the Rickman brothers yielded a similar Bultaco manufactured Mk 1 Pursang that was down right crude in comparison.

This example is 1 of 24 bootlegged into the U.S. in pieces by Charlie Hockie and Bud Ekins. U.S. Petite Metisse’s were painted British racing green. This example was restored by Matt Hilgenberg.

BULTACO PURSANG 250 MK4 MOTOCROSS MODEL / 1971

When the Mk. 4 hit the track (1971 and 1972) it was hailed as Bultaco’s best looking dirt bike ever. From the start, the Pursang was a deadly serious motocross competitor even if its long wheelbase, fork angle and low center of gravity also made it a true challenger in smoother dirt track competition. The engine was blessed with usable torque and strong top end power.

The Mk. 4 was sold in two versions, a scrambles model with a 19” front wheel, universal tires, and clip on handlebars, and a motocross model with a 21” front wheel, knobby tires, and cross braced MX style handlebar. This example is the motocross model and was restored by Vintage Iron.

The Pursang is especially dear to me as I rode a similar scrambles model with support from Bultaco in America through my novice professional year (1972). What an awesome slider with excellent usable power! THUMBS UP!

BULTACO 360 PURSANG MKVII / 1974

Bultaco had been a very successful brand in American scrambles racing since the mid 1960’s and enjoyed some success in motocross on a local level, but seldom on the national or international level. That would change when American upstart Jim Pomeroy shocked the FIM international motocross establishment by winning the 1973 250cc Spanish motocross Grand Prix. The news of his victory created a huge wave of excitement in America where motocross was undergoing an explosive growth in popularity. His victory signaled that American motocross riders were ready to compete with the best in the world and so was Bultaco.

Bultaco, founded in 1958 by Francisco Xavier Bulto, first introduced an open class machine in 1967 as the 350cc El Bandido. Early models were plagued with excessive weight and power that few riders could tame. By 1974 the 360cc Pursang was nearly identical in design to the production 250 that Pomeroy had ridden to win the Spanish Grand Prix. Claimed horsepower was 39 at 7000rpm……which in print favored well with other open class machines, but in reality, seemed like “A load of bull!” That was mitigated by the way the Pursang hooked up! Open class Bultaco riders felt like nothing cornered like a Bultaco and you could steer thru the turns with the throttle wide open. The lower than most seating position also favored riders under 6′ tall.

The 360 Pursang was a beautiful machine! It is often mentioned how the Spanish factory had dirt floors. That being said, the Pursang was an absolutely jewel! The engine cases were highly polished as were the fork crowns and the hubs. The fenders, side panels, airbox, and fuel tank were fiberglass with a very nice painted finish. Other niceties included Femsa ignition, Betor front and rear suspension, and Akront shoulderless rims with Pirelli tires.

BULTACO PURSAND MK2 250cc SCRAMBLER / 1967

The MKII Pursang would be a major change from the Rickman inspired MKI Pursang and only the engine would remain similar. The wheelbase was extended over 1 _” and the body work was distinctively square leading to many riders calling the Pursang the “Boat-tail” for its similarity to a sailing ship. Both a motocross model (21” front wheel) and a scrambles model (19” front wheel) were available in America.

For motocross, it could easily be argued that Bultaco went the wrong direction as the increased power was rather peaky and the longer wheelbase made quick changes of directions difficult. Fortunately, this proved to be just what scramble riders in America wanted for the higher speed and smoother tracks. Out of the crate, the MKII put out 34 horsepower, a good 5 horsepower more than many of its European competitors. The fiberglass body work was absolutely beautiful, but unfortunately was easily damaged the first time the rider would fall down. The high pipe also over-heated the rider’s right leg and bottom and would give way the next year to a low pipe.

Amazing that such a beautiful machine was made in a Spanish factory with dirt floors.

Restored by Bob Benson the machine is now owned by the The Early Years of Motocross Museum.

BULTACO EL BANDITO 360 / 1968

The Spanish Bultaco El Bandido first appeared in 1967 as 350cc model and in 1968 the bore was increase from 83.2mm to 85mm which gave it 362cc and 43.5hp. Therein lays the problem! Weighing in at 251lbs, some 20 pounds heavier than the 250 Pursang and with almost 10 more horsepower, very few riders were capable of taming the Bandit!

Spanish metal was often blamed for the poor reliability of the Spanish brands – Bultaco, Ossa, and Montesa and the problem was only accentuated with the big bore El Bandido. The machine also used a Femsatronic electric ignition that would prove to be unreliable.

As with the 250cc Pursang models, the Bandido was available in both motocross and scrambles models. In America, far more scrambles models would be sold as the longish wheelbase (55.9”), 31 degree head angle, and ample power was better suited to smoother scrambles tracks.

Though they are largely ignored by AHRMA racers they have become a very desirable collector bike. Because there were relatively few sold in America, nice original machines command a high price. Let’s not forgot how beautiful the El Bandido is when restored to like new condition. This handsome example was restored by Steve Morris.

CAN-AM 250cc MX2 / 1975

Known affectionately as the “Canned Ham,” the Canadian-built Can-Am MX2 was a uniquely different machine from what was offered by the Japanese and Europe marques. The Austrian-built Rotax engine used a rotary valve intake system. The 32mm Bing carb was mounted behind the engine and the fuel was fed to the lower end via a tuned 30mm aluminum tube. The smaller intake tract increased fuel velocity so that when the pie-shaped rotary disc opened up the fuel would go directly into the lower-end. Rotary valve engines enjoyed popularity in the early 1970s on Kawasaki dirt bikes, most notably the 350 Big Horn, and on later-generation four-cylinder two-stroke road race engines. A unique feature included a gauze-type air filter that sat on top of a still-air box (air was drawn into the engine via a vent where the rear fender met the seat).

The 1975 Can-Am MX2 was based on the bike that Gary Jones, Marty Tripes and Jimmy Ellis used to sweep the 1974 AMA 250 National Championships.

COTTON COBRA 250 / 1965

The Cotton marque was actually founded in 1918 by Frank Willoughby Cotton as a sporting street motorcycle with a unique for its time triangulated steel tube frame. It wasn’t until 1961 that Cotton which had gone through several ownership changes entered the scrambles market. At that time the 250 Cougar Scrambler was introduced and a works racing team was formed with riders Bryan “Badger” Goss and John Draper.

Though the Cottons were similar in many ways to the Greeves and DOT motorcycle that were also manufactured in England with proprietary components, several features quickly distinguished the Cougar Scrambler. For one, the Villiers engines were set back and down in the frame and used the lightest tubing available. Match this with the very beefy Armstrong leading-link front forks and you had a very different, if not ugly motorcycle.

The theory of keeping the main weight distribution over the rear wheel and the center of gravity low, worked well in practice, though riding a Cotton was an acquired taste. These were low ground clearance wheely machines which needed to be ridden solely on the rear wheel.

The American models came with a 19” front wheel and an 18” rear wheel with the Metal Profile hubs used by most of the English manufactures. The power plant was standard issue Villiers Starmaker engine with claimed horsepower output of 26 at 6000 rpm’s and a 4-speed gearbox. Rear shocks were by Girling, fenders were chromed steel, and the standard fuel tank was a 2 _ gal steel tank though a 1 _ gal fiberglass was available for motocross.

Any hopes of real motocross racing success came in 1964 when BSA factory rider Arthur Lampkin switched over to the Cotton brand for a few races. Unfortunately he wasn’t impressed and returned to BSA to finish his career. Cotton sales never took off in America and the company closed down in 1980.

CZ250 TWIN PORT / 1965

CZ’s twin port 250 and 360 were the final nails in the coffins of the four stroke behemoths when the Czech factory rewrote motocross history in the mid 1960s.

The twin port 250 was a replica of CZ’s own works GP bike, yet marked the close of one era for CZ as the new 360cc set the factories rules of motocross motorcycle technology for the next decade. Check out the CZ360 in the museum to compare the newer technology compared to the 250 twin port.

In 1964 Joel Robert won the 250 World Championships on a bike very similar to this example. The next year, Russian rider Viktor Arbekov echoed Robert’s ’64 title win to elevate CZ to the high ground that Husqvarna’s Torsten Hallman had previously enjoyed.

According to the seller, this machine was restored by Joel Robert’s factory mechanic. This is an example of the myths that often surround the purchase of a Czech motorcycle. When buying a CZ, caviet emptor (buyer beware) as the history of the Czech motorcycle can be sketchy and so can the characters that trade them.

CZ250 FALTA REPLICA / 1975

In 1975 there was host of Japanese entries into the highly competitive motocross market. The CZ factory in Czechoslovakia responded with a machine that closely resembled the “works” bike the Jaroslav Falta had “almost” won the ’74 250cc World Championships with.

Let me explain the almost! Moving into the final round of the 250cc World Championships in Wohlen, Switzerland, Russian KTM rider Gennedy Moiseev held a slim 16 point lead over Falta. In what appeared to be coop, Russian riders Pavel Rulev, Viktor Popenko, and Rabalcenko used a racing strategy that constituted a race-long assault on Falta culminating in an incident that became known as the “Popenko T Bone!” Many spectators claimed that the Russians intentionally rammed Falta, forcing him to crash in both motos. Falta would fight back to win both moto’s, but the Russians would then protest the results, saying that Falta had jumped the starting gate. The FIM jury sided with the Russians and relegated Falta to second place for the race and out of the 250cc World Championship by a couple of points!

In the summer of 1974, Falta traveled to America to compete in a few Inter-Am events and also at the LA Coliseum Superbowl of Motocross. In front of 65,000 spectators, Falta would take his CZ to first place beating all of the American hero’s including Roger DeCoster. CZ was back!

The ’75 Falta model featured the key components of the factory bike and also satisfied CZ’s core values of performance and indestructibility. Standard features included the alloy-bodied airshocks that were unique and effective, magnesium hubs, lipless alloy rims, and a hand-made leather belt that secured the alloy fuel tank. With the single-tube red frame and improved styling, the Falta had shaken the agricultural look that the CZ’s were know for.

The 1975/76 CZ250 and 400 Falta Replicas were nearly identical.

CZ360 / 1969

Arguably the best open class motocrosser available to the public in 1969, the CZ360 was still a beast to ride. Hampered by a dual plug ignition that would jump timing often, a Jikov carburetor that flooded easily, and heavy vibration, it was still better than most.

The Czechs were rightfully proud of the reliability and construction of CZ models. When I attended CZ mechanics school in 1969, Stan Cerney, the instructor bragged how the CZ gearbox would easily withstand full-throttle, clutch-less, stab-it-into 1st gear starts. I still remember the morning, lunch, and afternoon breaks at the CZ school. Mr. Cerney would bring out a case of beer to share with the class during these breaks, and of course, the more beer – the better the CZ’s were.

This example was raced in the desert and when I purchased it from my friend, Matt Hilgenberg, it was what we call “a nearly perfect core” that was ready for restoration. Vintage Iron did the restoration.

CZ400 / 1972

Possibly the best open motocrosser ever produced by the Strakonice, Czechoslovakia factory, the writing was on the wall for European motocross bikes. Though the best open class Japanese offerings had yet to hit the market, Roger DeCoster and Joel Robert has jumped ship to win World Championships for Suzuki in the 250 and 500 Championships.

The 1972 was little changed from the late 60’s model. Engine performance was hampered by the Jikov carburetor and the magneto ignition. The 400 was also heavy, but on the positive side, the CZ was known to be extremely reliable. Extra care was taken at the CZ factory on assembly to measure parts and actually blue-print engines to assure quality.

Riding the CZ400 was hard work with abrupt power delivery and heavy vibration. Fortunately suspension action was good, especially if the Tria shocks were traded for Koni or Girling shock absorbers.

This bike came from the Bertus Bertus collection and was reported to be original an un-restored. Is so, they don’t get any better than this example. Enjoy!

DKW 125 MOTOCROSS / 1971

This German machine was produced about the same time that corporate restructuring transferred ownership interests in the bike from Sachs to DKW. The engine cases carry the Sachs name, while the tank badges reflect DKW’s proprietary interest.

The two-stroke single was specifically built to be a contender in the 125cc motocross class, which was in growth mode and destined for world championship status starting in 1975.

The DKW was quick and its leading-link Bode front suspension added to its stability. At $750 retail it was considered pricey, but it delivered quality commensurate with its cost.

The DKW name dates to the early twentieth century and originally stood for Dampf Kraft Wagen or steam-powered car. Later variations included Des Knaens Wunsch (the boy’s wish) and Das Kleine Wunder (the little miracle). Whatever DKW stood for in the German language, it stood for quality small-displacement motorcycles in the early 1970s marketplace.

DUCATI 450R / T DESMO / 1971

Ducati sprung to life by making a small bicycle engine to transport the war-ravaged Italian citizens. In 1946, the Cucciolo (little puppy) engine was originally sold in a box to be attached to a bicycle. Before WWII, Ducati had produced radio tubes and condensers, but thanks to the Cucciolo’s success, Ducati became a name brand motorcycle manufacturer. By 1954, Ducati was producing 120 bikes a day. Even more momentous in ’54 was the arrival of engineer Fabio Taglioni. Taglioni’s big idea was to control valve float by having the valves positively opened and closed without using valve springs. The main benefit of his desmodromic system was the prevention of valve float. Valve float can cause a catastrophic collision between the piston and valve or, at the very least, create poor valve seal. The desmodromic system eliminates valve float by using dual rocker arms on each valve (one for opening and one for closing the valve). The Ducati 450 R/T was the first and only motocross bike to be outfitted with desmodromic valves.

DUCATI 750 F1B / 1986

ESO 500cc Moto-Cross / 1959

Black Swan or ugly duckling – a question of perspective on this Czech scrambles machine manufactured near the Jawa factory. Eso’s were always limited production machines that ended up in the hands of the best club racers and GP riders. This helped create a mystique that lives to this day.

Taller, longer, and a little heavy compared to the British 4-strokes, the ESO was fast! The engine, the masterpiece of the ESO, was well ahead of it’s time in terms of engineering. Straight cut gears (no primary chain), unit construction, and a crankshaft that spins backwards are amongst the unique features of the ESO. The chassis measures 1” longer than the Goldstar and other popular 4-strokes and when combined with a few more degrees of rake, is a slow responder. Better find a berm!

This example is a 2-time Del-Mar Concours show winner that I’m sure you will enjoy.

Greeves 250cc Anglian Trials / 1967

Magazine test rider, Mike Bashford states in the October 1966 test of the Anglian, “The Anglian sets a hard-to-beat standard for a trials bike.” He goes on to comment on the instant power that could be re-applied – not desperately, but gently and smoothly – after a near-stop on a steep bank.

The Greeves Anglian was a benchmark for performance and reliability for a Trials machine. The Anglian was available with the standard leading link forks and/or for about $50.00 more, a Ceriani telescopic model was also available. Traditional Greeves riders preferred the leading link, while newer riders preferred the telescopic fork.

American riders Tibby Thibodeau and Al Gendreau won the 1966 and 1967 New England Trials Championships on the Anglian. At the time, the New England Championships were the premier Trials event in the USA.

This example was lovingly restored to original condition by Matt Hilgenberg.

Greeves 250 Starmaker 24ME / 1963

By the end of the 1962 season the Greeves-modified 34A Villiers motor as used by the factory riders was beginning to show signs of fatigue. Not surprising as Greeves had increased the power by over 25% from the original Villiers engine. This was accomplished by using an aluminum cylinder featuring better porting, a larger carburetor, and improved exhaust design. Unfortunately, transmission, clutch, and crankshaft problems were becoming all too common. Out of frustration with Villiers, Greeves started development of its own engine.

Not wishing to lose the Greeves business, Villiers started development of and all new engine dubbed the Starmaker. It was a radically different design from the previous engines with a strengthened crank, duplex primary chain, and redesigned clutch and transmission. The most notable feature was the use of dual-Amal Monobloc carburetors that were set to open progressively. The hope was better bottom end power and high power at high speeds. Power output was promising at a reported 25 bhp at 6500 rpm.

In 1963, Greeves introduced the new Starmaker utilizing the new Villiers engine and for the first time a quieter exhaust that had been mandated by the ACU (Auto Cycle Union). The new model was designated the 24ME. The production run was only 89 units as Greeves had little confidence in the design.

Unfortunately Greeves was right. The machine was so bad that factory rider, Dave Bickers switched to rival brand Husqvarna in mid season. Many of the dealers that purchased these machines couldn’t even get them to run and customers were demanding own engines refunds. This signaled the end of the Greeves/Villiers relationship and Greeves began manufacturing their.

Greeves 250cc Challenger 24MX5 / 1967

Bert Greeves never planned to become a motorcycle manufacturer. Tom White never planned to have a motorcycle museum. While this bike was the culmination of Greeve’s early years of building invalid carriages, this machine was the start of Tom’s collection.

Greeves was by far the most popular off-road 2-stroke in America in the early 1960’s. With its Earl’s type forks and aluminum I-beam frame, Greeves was easily distinguished from other brands. This example, the 1967 Challenger was at the beginning of the end, so to speak in the popularity of the Greeves motorcycle. As motocross mania swept America, the lighter-weight Husky’s and CZ’s became the tool of choice.

Top Greeves riders included Dave Bickers, Bryan Wade, and Gary Bailey. Please enjoy this fine example restored by Denny Berg back in 1989 when he owned the Time Machine Motorcycle Works.

Greeves 380 Griffin (1969)

Harley-Davidson Baja 100cc (1971)

The Harley Davidson Baja 100 was actually made by the Italian company, Aermacchi for the American market. This little dirt bike was raced in scrambles, motocross, and in desert events. The California desert is where the Baja really shined. For one thing, unlike motocross, desert racing had a class for 100cc machines. The Baja’s abundant ground clearance, and good suspension – they used Baby Ceriani forks, was a real factor in the desert events.

Rider like Bruce Ogilvie, Mitch Payton, and Mitch Mayes all got their starts racing Bajas in the District 37 Desert trailbike class. Unfortunately, Harley Davidson gave up on this fun motorcycle to concentrate on the heavy iron which they were known for.

One thing I’ve discovered since jumping into the vintage dirt bike market, is the enthusiast that have come to the rescue of a certain marque. In this case, the Baja expert is a gentleman named Rudy Pock. He has gathered a warehouse full of bikes and parts, done a lot of research, and has restored many Bajas to factory original. This example was restored by Rudy.

Harley-Davidson MX-250 (1978)

Harley-Davidson’s entrée to the world of motocross was a by-product of one of the most unusual marriages in motorcycle history when they purchased Italian firm, Aermacchi in 1960. This marriage gave them access to a basic 2-stroke engine and the rapidly developing MX market in America.

After some success with its prototype in 1975, the 1978 MX-250 was put into production. Unfortunately, even with riders like Rex Staten, Marty Tripes, and Rich Eirstadt, the results were lackluster. Although the power of the Aermacchi engine was excellent, the weight (249lbs) made it portly, the suspension lagged against the other Japanese and European offerings, and the price ($1695) was $250 to $300 more than the Suzuki RM and Yamaha YZ.

Harley’s relationship with Aermacchi ground to a halt after 1978 because of environmental concerns with 2-strokes and the MX-250 ceased production.

This un-restored example was 1 of approximately 1000 built in the only year of production, 1978.

Harley-Davidson XR750 – “Alloy XR” (1972)

The XR750 that you are looking at was number 009 of 190 examples built by Harley-Davidson in 1972. The “Alloy XR” was the brainchild of race-team manager Dick O’Brian. Frustrated by reliability problems and lackluster power from the “Iron XR,” Mr. OBrian and his staff set about building a production racer that could beat the Triumphs, BSA’s, and Yamaha’s that were winning the majority of Grand National events.

Of the 80 motorcycles I currently own, this is the first complete restoration I have undertaken. It was a blast! My brother Dan (my tuner) and I raced a similar example in the 1973, 74, and 75 seasons. My National Number was 80 and we had pretty good success competing against my hero’s – Kenny Roberts, Gary Scott, Mert Lawwill, Gene Romero, and the other top national dirt-track pros. Over 30 years have gone by, but I instantly became reacquainted to every nut and bolt on the production XR750.

This bike was returned to factory “out of the crate” original. Hope you enjoy this lovingly restored example of dirt-track racing history!

Harley-Davidson CRTT Sprint (1968)

In 1968 TT racing was very popular. TT or tourist trophy as it was called, was a smooth track competition with right and left hand corners, and usually a jump. Harley-Davidson, with the help of their Italian partner, Aermacchi built a 250cc 4-stroke that was well suited to this type of racing. The Sprint model was quite popular from the mid 1960’s until the early 70’s when most riders either rode 2-strokes in TT’s or switched to motocross, which was becoming the sport of choice for many American riders.

The Sprint was available in 250cc and later in a 350cc version, and also in a fully street legal version with lights and other necessary equipment. Harley Sprint street models were considered entry level machines for female or newer riders that didn’t have the experience to handle the big dressers.

This machine came from Bob Tryon who was part of the management team at BSA/Triumph in the early 1970’s.

Hodaka 100cc Super Rat (1971)

Originally introduced in America by the Oregon distributor Pabatco (Pacific Basin Trading Co.) in 1964, the Ace 90 was an immediate success. And inexpensive, fun dirt bike that literally, could be ridden hard and put away wet.

By 1971 the Ace 90 was bored to 100cc and featured many refinements. The new name was “Super Rat,” and they could be found at off-road venues all over America. Aftermarket companies, like Webco in Venice, California sold hop-up parts like high compression cylinder heads, expansion chambers, higher flow airboxes. These parts were scooped up by the enthusiasts that were looking for and edge, or just “to be trick.”

This is another one of the bikes that found me! I’ve been fortunate that restorers with good bikes tire of them, and/or need money for new projects. The rumors out to “call Tom, he’ll pay double what its worth.” I paid $2500 for this bike – try and restore one for that!

Hodaka 125cc Super Combat / 1974

While the $900 Super Combat was the most advanced Hodaka ever made, it wasn’t built by a megabuck company with the finances to retool every year. So when the CR125 and YZ125 leapfrogged over the Hodaka in ’74, Hodaka racers were forced to improvise. By 1974 Hodaka’s most famous riders (Tommy Croft, Cordis Brooks, and Jody Weisel) were being tempted away from the Oregon-based company. To stem the tide, the most advanced 125cc Hodaka ever made was commissioned to be built (thanks to the support of Hodaka executive Marv Foster).

The list of innovations includes: Alex Steel coffin tank; ultra-long Swenco swingarm; RC-style shock positioning; 34mm Kayaba forks; Rickman conical hub; GP Specialties up-pipe; invisible silencer; CR-style seat; and lots of welding.

In the end, Hodaka closed its doors, the Super Combat died and the chosen rider, Jody Weisel, moved to Motocross Action. Through it all, this one-off, hand-built, 1974 Hodaka Super Combat still looks brand new.

Honda 50

Honda CR250M Elsinore / 1973

Announced in October of 1972 and on sale in the USA in March of 1973, the Elsinore was preceded by minimal hype but nevertheless generated great expectations.

Compared to the European offerings, the Elsinore was miles ahead in user friendliness, ergonomics, carburetion, durability, and electrics. The stark, conservative styling with moulded plastic, satin finished aluminum and the use of magnesium in the engine cases became the new standard. As you can imagine, Elsinore’s became as popular as free beer.

Gary Jones was hired to race the Elsinore in the ’73 Nationals and he reward Honda with its first 250cc National Championship and then backed it up in 1974. Production ’74 Elsinores were almost identical to the 1973 model.

Please enjoy this beautifully restored machine that was purchased from my friend, Greg Primm.

Huskqvarna 125cc Cross (1974)

The Husqvarna 125CR was produced from 1972 until 1985. It was often hard to tell one model year from another and this example sports 1974 engine numbers in a 1973 frame. Even more confusing, the gas tank logos changed in font and color between 1973 and 1974. What is true is that at the time of its release the Husqvarna 125CR was the most expensive 125 motocross bike a rider could buy. Unfortunately for Husky, it was released at almost the same time as the first Yamaha YZ125 (and only preceded the Honda CR125 by a short period of time).

Husqvarna suffered the same fate as many of the other European motocross bike manufactures as the Japanese machines kept getting better and better. In 1987 the Swedish brand was sold to Cagiva and production was moved to Italy. In 2009 BMW purchased the brand from Cagiva and the brand is becoming a premier brand once again.

This beautiful machine was restored by Frans Munsters, a Dutch collector and restorer.

Husqvarna Silverpilen 175cc MC-28E / 1960

When Husqvarna introduced the 175cc Silverpilen in 1995, Swedish young men were drawn to this lightweight and racy looking machine. The black and red paint job along with generous use of lightweight alloy components was a good base, and soon a healthy aftermarket for accessories would develop.

The lightweight (165lb) machine with a mere 9.5HP output was a perfect starting point for many tuners and the Silverpilen would receive many modifications aimed at either road racing or motocross. Gote Lindstrom was one of the young tuners that developed a reputation for his “hot rod” parts for the Silverpilen. By 1959, Lindstrom had developed a 250cc cylinder, high compression cylinder head, modified crankshaft, larger 32mm Bing carburetor, and an expansion chamber exhaust. Another Swede – Gustav Flink also built intake manifolds, cylinders, and heads for the machine, but took it another step farther by building a 250cc engine that would bolt into the stock Silverpilen chassis.

Both Lindstrom and Flink would go on to manufacture their own motorcycles; similar in many ways to the Silverpilen, but with 4-speed transmissions (instead of the 3-speed), 250cc engines, double cradle frames, and improved forks and shocks.

Future World Champions Torsten Hallman and Rolf Tibblin would get their racing careers started on modified Silverpilens. Husqvarna started taking notice and by 1963 had incorporated many of the tuners ideas into the new 250 cross models. Stronger frames and sub-frame sections, telescopic forks, Girling shocks, and a full 250cc engine would become standard.

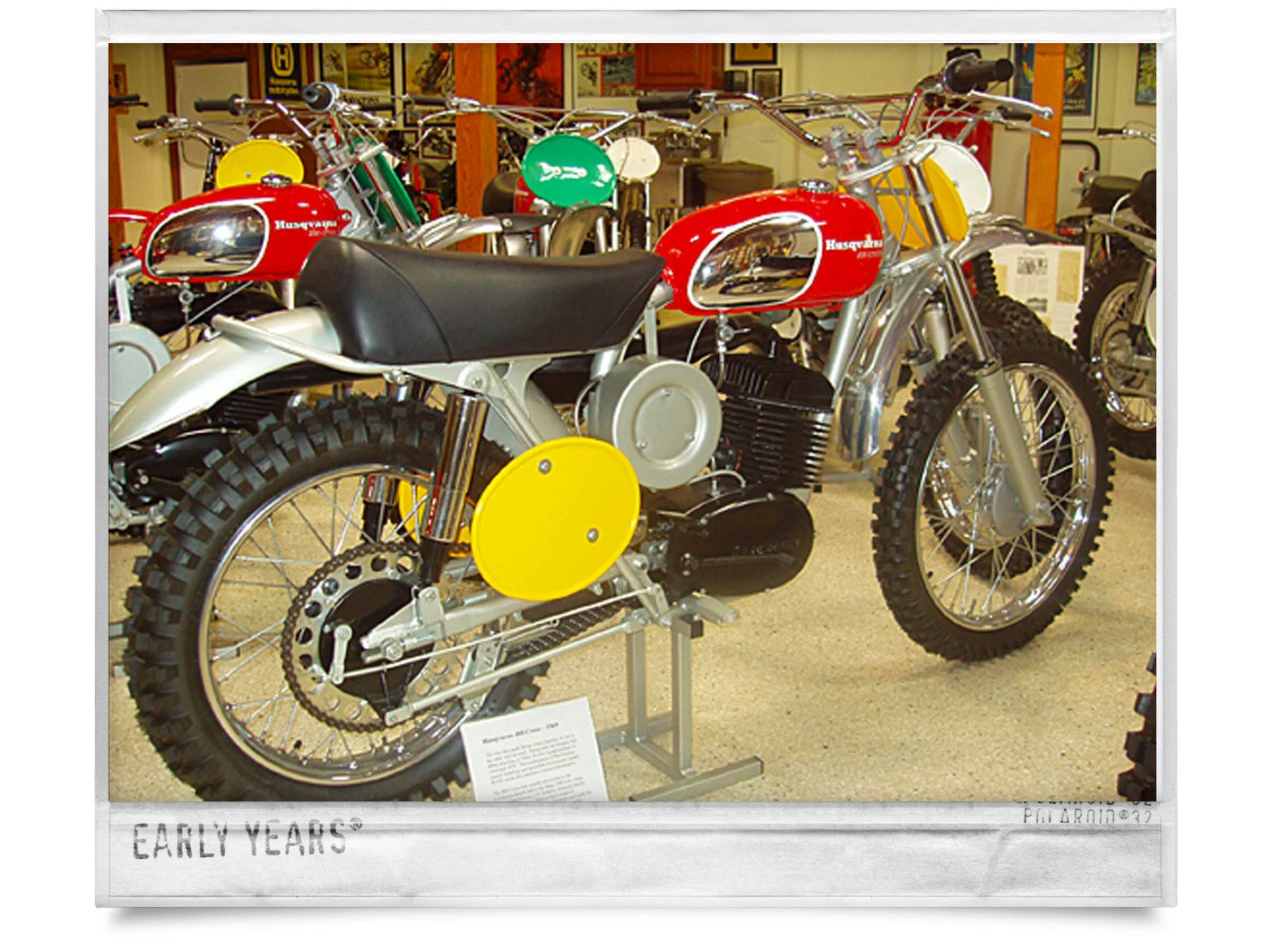

Husqvarna 250cc Cross / 1966

Edison Dye’s vision was to see European Moto-Cross become as popular in America as it was in Europe. In February of 1966 he imported two motorcycles, one of which would go to the legend, Malcolm Smith. By the fall of 1966, he had convinced Husqvarna to allow the then, 3-time World Champion Torsten Hallman to race in a series across American that would showcase Torsten (and the Huskies) abilities against the best riders in America.

Torsten Hallman was undefeated in 22 straight motos, often lapping the field in what would be the first Inter-Am series.

This example, one of approximately one hundred 250cc Cross’s imported and sold in 1966 was restored by collector Mike Owens. Note that the 1966 had a 19” front wheel, small crankcases, and bolt together frame. 1966 and 1967 models also were painted a burgundy color.

A handful of pre-1966 Husqvarna’s made there way to America, but 1966 was the first year that they were imported in significant numbers.

Husqvarna 250cc Cross / 1969

By 1969, Torsten Hallman, the 250cc World Champion in 1962, 1963, 1966, and 1967 had found a formidable competitor in the Belgium Joel Robert. The CZ rider won World Championships in the 250 class in 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, and 1972. The 1971 and 1972 Championships were won on the Japanese Suzuki RH. To this day, Torsten and Roger DeCoster consider Robert to be possibly the most talented motocross racer of all time.

In America, sales for the 250 Cross model were robust, as you could race this machine out of the crate with little or no modifications. Edison Dye picked only quality dealers to sell his Swedish Iron and demanded that they stock adequate parts supply to assure the riders and racers wouldn’t miss important events. I’m sure this contributed to the sales success.

This machine was meticulously restored by Bill McNees to better than new. Bill is one of the for-most restorers of Huskies, as his bikes have won the Del-Mar Concours several times. They don’t get any nicer than this example.

Husqvarna 250cc Cross / 1971

It was 1971 and Husqvarna motocross and off-road racing motorcycles were at their peak in popularity. The Japanese invasion was just coming on, but for the most part, the Asian imports were still considered play bikes. This was soon to change!

In many ways, the 1971 Husqvarna 250cc Cross was similar to the first 1966 model that hit American shores. Refined for durability, they still had a 4-speed transmission, the engine was almost identical in appearance, aluminum fenders replaced the steel fenders, and Akront alloy rims saved weight and were stronger than the predecessors steel rims. In function, the Huskies still shifted on the right while most of the competitors had moved shifting to the left. Much was to change the next year as Husqvarna tried to retain it’s position as the top motocross machine.

This machine was restored by Noble Butler to it’s original condition.

Husqvarna 250cc Cross (1972)

The 1972 250cc Cross was a completely new and redesigned motorcycle after years with no significant changes in the Husqvarna offerings. The engine now shifted on the left, like other European and Japanese machines, had an all new 5-speed transmission, and was considerably heavier than its predecessors. It’s rumored that several of the Husqvarna team riders actually refused to ride the new 5-speed models, and instead, rode the previous year’s model. They found the new engine less powerful, and for off-road, preferred the 8-speed (4-speed with hi/lo range) gearbox from the 1971 machine.

Fortunately for Husqvarna, due in large part to the success of the movie “On Any Sunday” that featured Malcolm Smith and Steve McQueen riding Huskies, sales continued to climb.

Purchased from my friend Mike Eber, the completely original machine was restored by Vintage Iron. It sits in the back of my son Brad’s prize 1970 Chevrolet El Camino. We hope and pray that Brad will someday take the Husky out to the desert for a ride in his beloved El Camino.

Husqvarna 250cc CR MAG / 1974

When Husqvarna first introduced the all new 5-speed models in 1972, most riders detested the heavier weight and poor performance of the new machines. This was all rectified in 1974 with the introduction of the 250 Mag model.

The Husqvarna factory had listened to the owners complaints and the new model featured magnesium (much lighter than aluminum) components throughout the machine. The engine center cases were even cast out of magnesium and the result was a much lighter machine. Performance was addressed with an all new reed induction engine that delivered stellar performance. The frame also received mods that improved the strength and suspension travel.

The 1974 250 CR MAG was and to this day….is considered by many as the best Husqvarna ever built. This example was restored to showroom new condition and purchased from the Brad Morrison collection. Enjoy!

Husqvarna 250 CR / 1976

Husqvarna 360cc Viking (1966)

Two-strokes made their first impact in the 250 class, where the woefully underpowered four-strokes quickly succumbed to the light weight and snappy response of the 250 offerings of CZ, Greeves and Husqvarna. But the naysayers claimed that two-strokes would never dominate the 500 class, for three reasons:

(1) The limited metallurgy of the day wasn’t conducive to two-stroke longevity (and a bigger piston only meant a shorter lifespan).

(2) A 500cc four-stroke could pump out more horsepower than a 360cc two-stroke.

(3) BSA, who owned the 500 World Championship, was ready to unleash titanium frames, ultra-lightweight engines and Jeff Smith on the horde of ring-dings.

Husqvarna had historically been part of the four-stroke power elite. Swede Rolf Tibblin had won the 1963 500 World Championship on a specially built Husky thumper that was never put into production. In 1963, the best two-stroke was in ninth place and no two-strokes finished in the top ten in 1964. It wasn’t until 1965 that the first two-stroke appeared on a 500cc podium when Czech-built CZ’s were second and third behind Jeff Smith on the four-stroke BSA. One year later, CZ-mounted Paul Friedrichs and Rolf Tibblin won nine of 14 500 GPs between them, signaling the end of four-stroke dominance.

Where was Husqvarna? They had pulled out of the 500 class to concentrate on building a competitive 250cc two-stroke for Torsten Hallman. That move paid off with back-to-back 250 World Championships in ’66 and ’67. Husky then used its 250cc development program to launch the 1966 Husqvarna 360 Viking. The Open class Husky was based on Torsten Hallman’s 250. Its 78.5mm by 72mm bore and stroke engine pumped out 37 horsepower (according to the brochure) via a 32mm Bing. As it sat, the 1966 Husky 360 weighed only 215 pounds.

This special Husqvarna, Serial #66939 is one of only ten, 1966 Husqvarna 360cc Vikings imported into the United States. It was only the second one delivered to Edison Dye in San Diego on July 6th, 1966 and was sold to Hertting’s Triumph Sales in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (see original sales invoice) a month later.

The previous owner, Brian Grade had this machine restored by John LeFevre to as new condition. This motorcycle may possibly be the only 1966 360cc know to exist in the United States today.

Husqvarna 360cc Cross / 1968

The 1968 Husqvarna Cross models featured many significant improvements over previous Huskies. Most notably was the one-piece frame that replaced the earlier bolt-together frames. The tank paint color was now a bright fire-engine red and there were many refinements that improved performance and reliability. The 360cc models were more powerful, with excellent low-end torque, and had – what the riders considered a very useable powerband.

The 1967 Inter-Am series had been a spectacular success, and Edison Dye could sell every Husqvarna Cross he could get his hands on. The 360cc models were especially popular in the deserts of America, thanks to riders like Malcolm Smith and J.N. Roberts who were dominate in the long and fast off-road races.

The example you see here was restored by my friend Noble Butler back to assembly-line new condition.

Husqvarna Enduro 360cc Sportsman / 1969

Edison Dye convinced Husqvarna management to build a street-legal machine similar to the motocross models that were selling so well in the Americas. 1969 was the first year that Dye was able to import this model in large volume and the Sportsman was intended to compete with the Yamaha DT1-250 and other offerings from the Japanese.

Malcolm Smith showcased this new machine by riding it, and Gold Medaling in the International Six Day Trials in Spain. Unfortunately, sales never took off for this very special machine. Rather high tech stuff – like the 8-speed hi-low range, and a rather high retail price contributed to the poor sales.

This example was restored by my friend, Bill McNees back to factory original. It’s been shown once at the Del Mar Concours where it won best in class.

Husqvarna 400 Cross / 1969

The bike that made Bengt Aberg famous, or was it the other way around? Aberg took the Huskies full 400cc machine to 500cc World Championships in 1969 and 1970. The combination of the Huskies precise handling and incredible horsepower (nearly 40 HP) made this machine a motocross weapon.

The 400 Cross was equally successful in the California deserts and in the Baja 1000 with riders like Gunnar Nilsson, J.N. Roberts, Malcolm Smith, and Whitey Martino. Edison Dye’s team of mechanics would mount large gas tanks and lights for the torturous Baja and the Husqvarna reliability would assure a good finish.

This example, built for me by Husqvarna expert, John LeFebre could almost be considered a new motorcycle. Over 50% of the parts used in the restoration were NOS (new – original stock) parts.

Please enjoy this excellent example of the Husqvarna golden years.

Husqvarna 400 Cross / 1970

Is this the Husqvarna 400 Cross that Malcolm Smith rode on the Baja beach in the movie “On Any Sunday?” Well……..no! But he rode one very similar to this example. Husqvarna was riding high and guaranteed more good karma with the introduction of this motorcycle documentory that was produced in 1970.

Arguably the most popular model ever produced by Husqvarna, this machine was the choice for many off-road racers included the actor Steve McQueen. Fast, excellent high speed handling, light-weight, and reliability were praises often sung by its owners.

How did I end up with so many Husqvarna’s? “They kinda find you,” is the answer to that. People find out you’re a collector of well restored Huskies and, if I don’t have that example, I get weak and make the purchase.

Please enjoy this well restored “On Any Sunday” bike. It’s as new on the inside as it is on the outside!

Husqvarna 400cc WR “Wide Ratio” / 1974

By 1974, Husqvarna had lots of competition in the off-road market. Honda had the Elsinore, Yamaha the MX and YZ models, Suzuki had the TM, and Kawasaki was selling the KX models. They – Husqvarna, sharpened their tool, so to speak, with this 6-speed, wide ratio gearbox model. Others features of the WR included a larger tank (than CR models), plastic fenders, and a much quieter muffler. Applause! They were ahead of their time with a quieter bike.

In the desert, with riders like A.C. Bakken, Brent Wallingsford, and Larry Roeseller, Huskie was still winning lots of races.

It’s interesting that Husqvarna chose to go back to the Burgundy colored fuel tank that they had abandoned in 1968.

This bike was restored to “as new” condition by Noble Butler.

Husqvarna 500cc Twin “Baja Invader” / 1969

If one cylinder is good, then two must be better! Or so thought Husqvarna engineer Ruben Helmen in 1966 when he designed production 250cc motocross components into a horizontal twin-cylinder engine. Without any major funds from his employer, he designed crankcases that could easily be cast by Husqvarna for mainstream production.

The motocross testing was handed over in 1968 to R&D rider, Rolf Tibblin and subsequently to 4-time World 250cc Motocross Champion Torsten Hallman. Hallman first raced the Twin on spiked snow tires before concluding that this was definitely no motocrosser. The engine was too wide, even though it was extremely fast. Unfortunately, the 500 Twin never made it to production and only one motocross/offroad version was ever built.

Baja Invader wins Baja 1000

In 1969, the 500 Twin was raced in the 5 European F.I.M. Cup motocross by Husqvarna rider, Gunnar Nilsson. The series, primarily to retain interest in the 501cc to 750cc sector that featured outmoded British 4-stroke iron, was easily dominated by Nilsson and the powerful Husky Twin. Fresh from this success, the bike was shipped to U.S. importer, Edison Dye. Edison’s vision was for this powerful machine to race the Baja 1000, one of the most grueling races on the earth. Riders, Gunnar Nilsson and J.N. Roberts were selected to pilot the machine. With speeds around 110mph, the 500 Twin won the 1969 event by 20 minutes. It was raced in several other events in 1970 and 1971 and then laid to rest in Dye’s warehouse for over 20 years.

Massive Motor

From the side, it’s very difficult to see the difference between the Twin and other early Husqvarna’s. Oh, but from the front or top, one is overwhelmed by the size, especially the width of the engine. This ex-Baja 1000 winner is the only Husky twin dirt bike ever built. It remained in Edison Dye’s former Husqvarna warehouse until 1998 when Dutch enthusiast, Frans Munsters purchased the bike and restored it meticulously to original specification. It now resides at Tom White’s Early Years of Motocross Museum.

Specifications

Engine: Piston port, 2-stroke twin, 490cc(69.5 x 64.5mm), 4-speed transmission

Power rating: 60hp @ 6500 rpm

Fuel System: 2 Amal Concentric 1 1/8”

Suspension: Husky telescopic forks-35mm, swingarm rear with Girling Shocks

Wheels/Brakes: 21” front w/drum brake, 18” rear w/drum brake – Akront rims

Weight: 265 lbs-dry

In reality, only 10 engines were ever built, with two going to road racer Bo Grannath, seven to European sidecar racing, and the Baja Invader.

Husqvarna 500cc 4-stroke Motocross / 1962

In the late 1950’s Nils Hedlund worked first with the Monark factory and then later with Lito to develop a start of the art 500cc motocross machine. Some similarities exist between these early machines and the BSA Gold Star. In fact, the Gold Star transmission was used in these exotic machines. Only 6 true Monarks were ever built and approximately 30 Lito’s.

In 1960 Husqvarna hired Hedlund to build race bikes for factory riders Bill Nilsson and Rolf Tibblin. Hedlund build 10 complete machines from 1960 to 61 and 6 machines in 1962. Bill Nilsson rewarded Husqvarna with the 1960 500cc World Champion and Tibblin won the 1962 and 63 World Championship for the Swedish marques. By 1964 Jeff Smith would win the 500cc World Championship on a smaller 4-stroke machine signaling the end of the 4-stroke behemoths!

In recent years several replicas have been built in Italy that appear correct in nearly every detail. Please enjoy this hand-built machine.

Husqvarna 250cc – U.S. Military Model / 1976

U.S. Army joined the off-road motorcycle revolution and ordered approximately 100 of these automatic transmission Huskies. The rear rack would support radios, extra fuel, or ammunition and accessory mounts could be added for rifles or automatic weapons. As you can see, the color was Army green and black – no chrome here as reflections could be seen afar.

Wish I had some great battle stories to tell you, help me out if you know some, but as far as I know the Husky Military Model was not responsible for winning any wars. The fact that the U. S. Army purchased the Swedish motorcycle helps confirm the popularity the Huskies enjoyed at the time.

This bike was meticulously restored by Noble Butler back to original – U.S. Army specifications.

Jawa 350 Twin

Jawa 500 Speedway / 1971

A limited production thoroughbred, the machine that has made the word “Speedway” and the name JAWA synonymous. That’s the opening message from Jawa’s sales brochure in 1971.

Speedway racing in America has always been mostly a West Coast activity. In the late 60’s and early 70’s, riders like Rick Woods, Mike and Steve Bast, and Wild Bill Cody were tearing up local tracks on the alcohol burning, bicycle like, speedway machines. Costa Mesa Fairgrounds was the place to be on Friday nights and the top riders had almost “rock star status.”

Almost 5 years ago, I contacted Bill Cody (ex-racer and Jawa importer) to find and restore an early model Jawa Speedway for me. The machine he found was raced by a former White Bros. employee and friend, Jimmy Odell. Bill painstakenly searched to find the correct, original parts for a museum quality restoration to “out of the crate” original condition.

Please enjoy this unique machine!

Kawasaki F21M 238cc / 1969

In 1968, Kawasaki joined Suzuki with a production off-road machine. Unlike the Suzuki TM250 that was targeted at motocross, the F21was designed for the smoother scrambles tracks of America. The color brochure said “Hit the Scrambles Trail on a Top-performer Built to Take it.

The actual displacement was 238cc and many riders just called the Kawi the 238. Possibly because of the displacement not being a full 250 like the European Bultaco’s and Ossa’s, and the Japanese Yamaha DT1, performance was sub-par and the Big Green Streak never took off. At the same time, Kawasaki made a 100cc Little Green Streak that flat flew and they flew off the dealer show rooms.

The engine was rotary valve inducted with a 4-speed transmission to distribute the 30 claimed horsepower. Weight was only 215 pounds.

This bike was restored by a Kawasaki enthusiast in the Bay Area to concours condition. Enjoy!

Kawasaki F11M 250cc / 1973

By 1973 the Japanese were realizing that a warmed over trailbike wouldn’t satisfy the growing motocross market in America and around the world. Though Kawasaki had been one of the first to introduce a 250cc class motocrosser – the F21M 238cc Scrambler in 1968, the machine was best suited to the smoother scrambles tracks in America at the time. Kawasaki followed in 1971 with the Big Horn Scrambler, a physically larger and much heavier machine that would prove to be a “dust collector” in the dealer showrooms.

Motocross was also becoming popular in Japan and the Japanese 250cc National Championships were becoming an important venue to compete with the latest and greatest machines from the other Japanese manufactures. In America, Kawasaki had hired Brad Lackey to compete in the 500cc National Championships aboard a factory works bike and he rewarded them with the 1972 500cc National Championship.

In preparation for the 1973 season, the factory initiated production of a semi-production machine (just 200 units) that was dubbed the F11-M. Most of these remained in Japan as the smaller Japanese riders didn’t have the size and strength to handle the open class machines that were so popular in America.

Bryon Farnsworth – Kawasaki R&D Manager in America recalls testing the early F11M prototypes coming from Japan. “We used Peter Lamppu and Jim Cook as test riders and Kawasaki Japan contracted Thorlief Hansen! Our riders were impressed with the power, the finish was good, but suspension and handling still left something to be desired!” Bryon goes on to say, “The Japanese focused on the 250’s as their test riders were smaller and we (Kawasaki R&D in America) focused on developing the 450 identified as the F-12MX! Heck, the Japanese test riders couldn’t even start the 450’s……..we had to do it for them!”

By 1974, Kawasaki introduced the KX line of motocross bikes and later hired Jeff Ward, Gary Semics, and Jimmy Weinert to pilot the factory machines. Weinert rewarded them with a 500cc National title in 1975 and a 250cc Supercross title in 1976.

Kawasaki Works KX125 / 1991

Coming into the 1991 125cc AMA National Championships, Kawasaki hadn’t won the series since 1984 when Jeff Ward took the championship. Kawasaki was looking for a rider that could win the tiddler class and Mike Kiedrowski was looking for revenge after being dropped by the Honda factory team at the end of the 1990 season. Kiedrowski had won the ’89 125 Championship for Honda and had finished just one point behind Suzuki’s Guy Cooper in the 1990 Championships.

Mike recalls, “Kawasaki hired me with the promise and understanding that I would win the championship for them! I felt a lot of pressure, but they gave me 100% backing and built the bike exactly the way I wanted it!” Kiedrowski’s mechanic was Shane Nalley with Rick Ash doing the suspension and Jim Felt building the motors. “MX Kied” as Shane called him didn’t have the fastest bike on the track, Mitch Payton called it a “Slug,” but it suited him perfectly and they tested and modified the production based machine extensively.

Some of the engine modifications included stuffing the crank to increase crankcase pressure and filling the transfer ports with epoxy and completely reshaping. Engine weight was saving by using magnesium primary and ignition covers and shaving material on clutch and transmission components. Suspension was “Works Kayaba” and fine tuned by Ash with an emphasis on high speed compression control that Kiedrowski demanded.

Mike Kiedrowski has graciously loaned the machine to the Early Years of Motocross museum! Thanks – “MX Kied!”

Kawasaki 100cc G31M Centurian

In the early 1970s the highly tuned G31M was a dominate force in Flat Track, Tourist Trophy, and motocross events on relatively smooth tracks. The “Baby Greenstreak” as it was often called, put out an astounding 18.5 horsepower at 13,000 rpm’s. The small tip or “stinger” on the expansion chamber gave the Centurian a distinct sound that is unmistakable to this day. The engine case was slightly different than other Kawasaki’s with the G31M having a secondary air intake on the carburetor cover. It also required the use of bean oil as a fuel additive for lubrication. Even then, lower end life was short because of the engines high rpm’s.

Actor Steve McQueen was given six G31M bikes by Kawasaki for the filming of the motion picture, LeMans. McQueen kept one for himself and painted it orange with gold stripes and gave it the name “Ringadingdoo.” The bike sold at an auction held at the Petersen Museum in Los Angeles in November of 2007 for an unheard price of $55,575.

Maico MC125 Motocross / 1968

How could one of the lightest, best handling and most powerful 125’s on the market not be a sales success? They say timing is everything and possibly the problem was introducing the potent 125 in early 1967, before 125’s became a major force in motocross. The 6-speed transmission was a similar design to that made by Sachs and if abused could easily develop 12 neutrals, though if adjusted properly, the trans was as sweet as any available. At nearly one thousand dollars, the little Maico was also almost double the price of its competitors.

The few riders that did step up to this marvelous machine experienced awesome handling as the chassis was the same as the 250cc and open class Maicos. If the road racing pipe, cylinder, and carb were installed, power was up to 25HP, more than many 250’s being sold at the time. Unfortunately in the late 1960’s and early 70’s there was no 125 World Championships to showcase the little Maico.

This rare Maico has been restored to Concours show condition. Please enjoy!

Maico 360cc Oval Barrell / 1967

The Maico 360 Oval Barrel was one of the first European open-class two-stroke machines to be imported into America. Imported by Frank Cooper, the early Maico’s seemed rather crude and didn’t generate much excitement in the US. Keep in mind, America was just starting to buy-in to the new European motocross bug and most riders were attracted to 250cc machines from Husqvarna and CZ.

In fact, the early open-class Maico was way ahead of its time. Leading axle forks and frame geometry that would allow the Maico’s to carve under other European brands was well matched with “torquey” power that easily transferred to the ground. On the negative side, Maico’s would gain a reputation for poor reliability that would stay with the marque for years to come.

This machine is begging for the correct handlebars. If you can help, please contact the Early Years of Motocross Museum.

Maico 400cc Motocross / 1973

By 1973, the Maico 400 and 440 models were the top choice of open class riders in America. Riders like German Champion, Adolph Weil showcased the big Maico’s well. Razor sharp handling, very linear and torquey power, and excellent suspension made the Maico’s hard to beat, especially on hard-packed track like Carlsbad and Saddleback.

Unfortunately, Maico’s also earned a reputation for poor reliability. “Maico Breako” and “Maico, Maico, made of tin, ride em out and push em in’ were often used to describe the German motorcycles. Fortunately, performance shops like Wheelsmith Engineering in Santa Ana were able to respoke the wheels, reline the brakes, fix the clutches, and make other modifications to improve the big Maico’s reliability. The 125cc and 250cc Maico’s were never popular, though both were also good handling motorcycles. The price was probably the biggest problem, though not much a barrier for the Open Class riders, who generally were older.

This example was purchased from a friend, Steve Donovan who did the restoration.

Maico GS400 / 1974

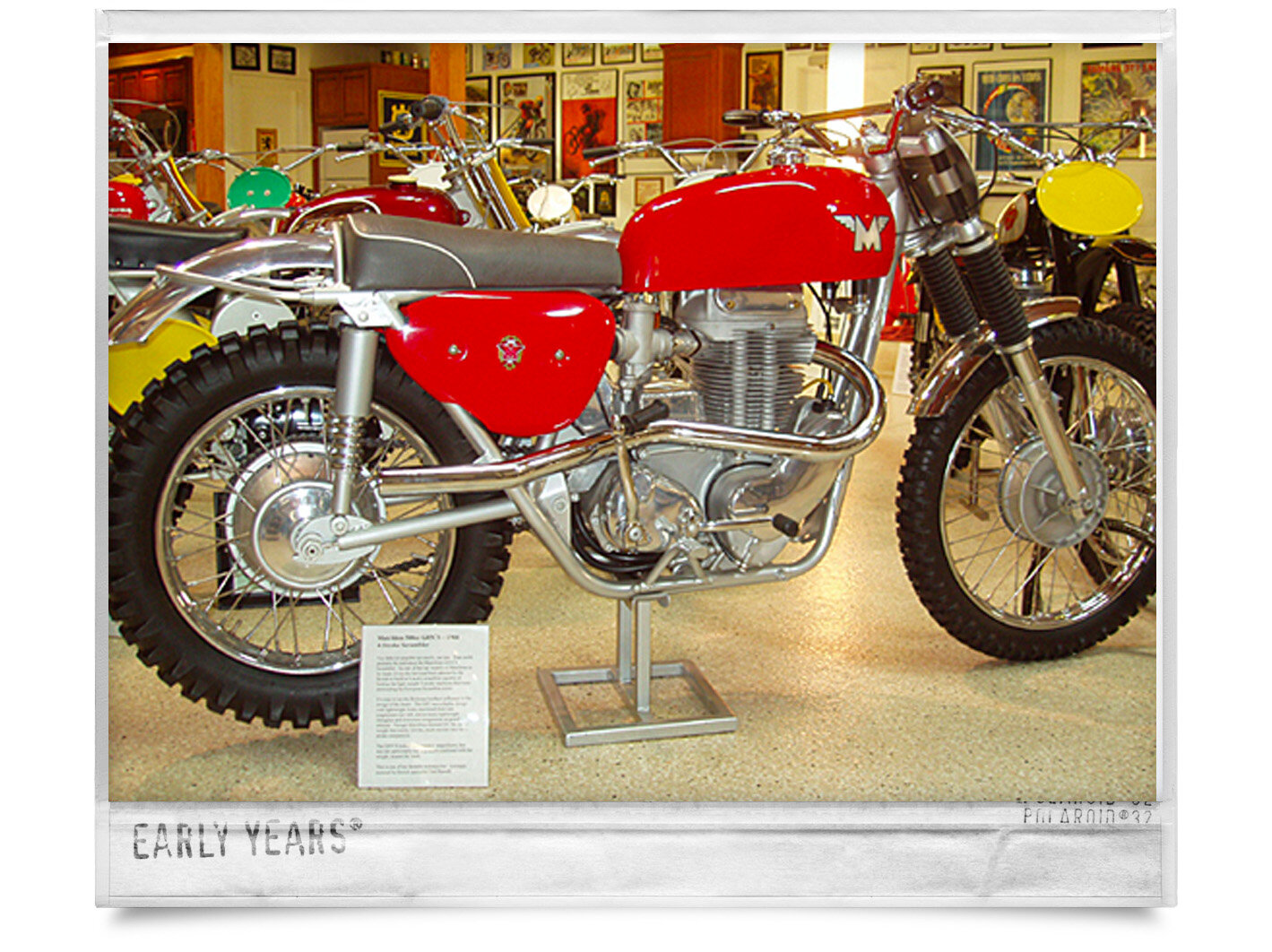

Matchless 500cc G85CS 4-Stroke Scrambler / 1966

Too little (or possible too much), too late. That could probably be said about the Matchless G85CS Scrambler. As one of the last models of Matchless to be made, it was the last (and best) attempt by the British to build a 4-stroke scrambler capable of beating the light-weight 2-stroke machines that were dominating the European Scrambles scene.

It’s easy to see the Rickman brothers influence in the design of the frame. The G85 was a duplex design with lightweight forks, machined front hub, magnesium rear hub, and as many lightweight fiberglass and aluminum components as possible utilized. Though Matchless claimed 291 lbs, actual weight was nearly 320 lbs, much heavier that the 2-stroke competition.

The G85CS looked and sounded magnificent, but was not particularly fast and when combined with the weight, missed the mark.

This is one of my favorite motorcycles! Lovingly restored by British specialist Don Harrell.

Monark 500 Motocross / 1959

Sweden was a major presence in early motocross, noted both for its talented riders and groundbreaking machinery, and Sweden’s Monark is one of the rarest motocross machines from the 1950’s and 1960’s. The marque enjoyed great success in the International Six Days Trials and achieved its motocross zenith in 1959, when Sten Lundin rode an Albin-powered Monark to the FIM World 500cc Motocross Championship.

From its birth in 1913 to its demise in 1975, Monark specialized in chassis and suspension development. The company relied on power from engine suppliers that included Albin from Sweden, Sachs from Germany, and Morini from Italy.

An intense rivalry between four-stroke bikes from Sweden and Great Britain raged throughout the early 1960s, but gave way to the other side of the Iron Curtain in 1966, when East German Paul Friedrichs captured the FIM World Championship on a Czech-engineered two-stroke CZ.

This Monark was purchased from a collector in Amsterdam, Holland who raced it in Vintage motocross. Frans Munsters, a friend from Veghal, Holland was instrumental in the purchase and obtaining correct period wheels and other components for the machine. The meticulous restoration was done by British expert Don Harrell and the machine is owned by the Early Years of Motocross Museum. Enjoy!

Monark 125cc MX / 1971

The Swedish company Monark actually began in the early twentieth century building bicycles. The production of motorcycles didn’t start until the late 40’s and 50’s and the factories prowness was ultimately achieved in 1959 when Sten Lundin won the 500cc World Motocross Championship.

In 1970, Monark introduced its first 125cc motocross model and imported the machines to the USA initially through Rockford Motors in Illinois and later thru Inter-Trends in Burbank, California. The Monark’s used the popular Sachs engine with state-of-the-art chrome moly frame and Ceriani suspension components. They instantly became the Ferrari of the 1/8 liter class!

Ray Lopez won this event on a Penton and Marty Smith finished in second place riding the Monark MX model. Unfortunately for Monark (and Penton), Honda would introduce the all new 125cc Elsinore later than year and that was the end!

Mondial 200cc Motocross / 1952

The Italian company – Mondial (French for World) was started by the Bosselli brothers in 1948. The first prototype, a 125cc dual overhead cam roadrace bike, was the basis for future racing machines. The engine was designed by Dr. Fabion Taglione who became the founding engineer for Ducati. In 1949, the first year in full production, the twin-cam engined Mondial roadracer won the 125cc World Championship. Racing success continued in 1950 and 1951 with two more World Championships – MV Augusta was the main competitor. Mondial was primarily a roadracing company, but did manufacture 7 or 8 125cc MX machines in the early 1950’s. These motorcycles were never in production, but instead, raced by factory riders. The Mondial motocross machines won a single Italian National Championship in 1952 racing against Moto Guzzi and Aeromachi. Unfortunately, the Mondial motorcycle company in Rimini, Italy was out of business by 1958.

The Mondial 200cc you are looking at was built by a factory employee with the permission of the Bosselli brothers in 1952 for campaigning privately. Purchased from Rick Weedon, Edoardo Vannucchi, a well-known motorcycle restorer in Italy brought it back to original condition.

Please enjoy this very rare Italian motocross bike.

MJS Trials

Montesa 250cc LaCrosse (1967)

It’s amazing that the Spanish were able to manufacture such pretty motorcycles in warehouses that were, by today’s standards, so pre-historic. Dirt floors, hand tools, and work stations instead of assembly lines were typical. Montesa was one of the big 3 motorcycle manufactures in Spain that included Bultaco, and Ossa.

The LaCrosse model was primarily ridden on scrambles courses in America. These tracks were much smoother than typical European motocross. The LaCrosse had good power, used a 19” universal tire that worked well on groomed tracks, and was pleasing to the eye. Reliability could be an issue, much of this attributed to Spanish metallurgy that yielded soft parts. Typically Spanish, the Montesa had good fit and finish, was attractive to the eye, and looked “fast” standing still.

This example was purchased from a collector in Texas who had the restoration done by Bultaco West.

Montesa 360cc Capra GP / 1969

The Spanish Montesa factory was late to the party, so to speak, with its open class entry – the 360cc Capra GP. Other European makers had a several year head start manufacturing open class machinery. Never the less, the Capra was a formidable machine.

The 360 Capra GP was available in two versions; a scrambles machine the came with blue bodywork, a 19” front wheel, universal tires, and rigid footpegs, and a motocross version with orange bodywork, 21” front wheel, knobbies, and folding footpegs. Typical Spanish, the Capras were beautiful, powerful, and worked better on the smoother scrambles tracks than they did on the rougher European style motocross tracks that were springing up all over America.

Probably the worst trait of the 360 GP was the starting. Cycle World Magazine said in its test of the machine, “It is, without doubt, one of the most evil starting machines CYCLE WORLD has tested. Even though they stated that in the right hands it could win in MX, scrambles, or desert racing, the Capra 360 GP never became a big seller. John DeSoto was probably the most well known pilot of the Capra.

Norton P11 750cc Scrambler / 1967